PROLOGUE: THE JOY OF (BAD) PAINTING

Painting is difficult. Whereas anyone with a half-decent eye and a camera can trick himself into thinking that he is a photographer, brush, paint and canvas are less forgiving. Here, a lack of aptitude will reveal itself without mercy, just as an amateur violinist can never hide his atonal scrapings.

And yet, the urge to create is not restricted to the talented alone. The ungifted, too, must answer the muse when she calls. But whereas some may choose to jeer at paintings of staggering ineptitude, to me the work of the honest amateur, moved to create even when all the evidence says he shouldn’t bother, is more inspiring than much of the effluvium that fills the halls of contemporary art galleries today.

As I drift, flaneur-like, through the thrift stores and antique malls of Texas I like to record particularly striking examples of dubious art. Today I share a few favorites with you, dear reader. But before we begin, a word of warning: if there are any children looking over your shoulder, you may want to usher them out of the room lest they be traumatized by a male nude that, once seen, can never be unseen. You have been warned.

PART ONE: OH, THOSE RUSSIANS

Friends 4 Eva by Unknown

We begin with this fine depiction of the Father of the World Proletariat and The Gardener of Human Happiness enjoying a game of chess, which I stumbled upon during my first visit to Moscow’s Izmailovo Market in 1997.

In fact, I mistook the long trail of impoverished people selling their meager possessions on blankets laid on the ground for the market, and so never actually made it to Izmailovo, a fantastical wooden structure filled with antiques and icons and Soviet posters. This candid portrayal of Lenin and Stalin stopped me in my tracks: it had the relaxed energy of a Sunday painter, as if Henri Rousseau had been born into Soviet Russia and liked to paint dictators rather than jungle animals. Rather than “bad” I would describe it as naive — in every sense of the word.

In the late ‘90s, it was rare to see portraits or depictions of Stalin as he had not yet made his Putin-era partial comeback as a military genius. Only the hardcore, the true believers venerated his image, and they did it without any support from the state. This, clearly, was a family heirloom that had seen service on the wall of an apartment somewhere, and as such it had survived Khruschev’s denunciation, Gorbachev’s perestroika and Yeltsin’s free market anarchy. It was now valued at the price of a bucket of potatoes. I bought it, and the old lady who sold it to me was able to stay alive another week.

The painting then traveled to Scotland, where it lived in my parents’ attic for two decades, and then to Texas where I kept it in the garage for a few years before attempting to put it on display in my library. But despite the honest enthusiasm of the artist, I cannot quite get over the fact that it is, at the end of the day, a depiction of one of the great murderers of all time having a chuckle with the architect of a historical catastrophe. So into a cupboard it went, where it will probably stay until I die.

Thrift Store Dostoevsky by Bernice Leeman

Marble Falls, a town in the Texas Hill Country, has neither marble nor falls, although there is a granite quarry and a plaque dedicated to an astronaut who once visited the local cinema. But the town is probably most famous for the immense slices of lemon meringue pie served in the Bluebonnet Cafe (Est. 1929).

One burning summer day, I walked into the local Goodwill and was immediately struck by a large portrait of Dostoevsky located at the back of the store. Was there a super fan of the tormented Russian genius living out here on the Colorado River? Marble Falls is not a particularly literary town: there is a used bookstore, but it doesn’t get a lot of foot traffic, although if you like mass market romance and Star Trek novels then you’ll probably find something to read on its shelves.

Of course, it wasn’t actually a painting of Dostoevsky, but I studied literary theory at the high watermark of postmodernism so I wasn’t about to let a small detail like the intent of the creator get in the way of my interpretation. The furrowed brow, the intense stare, the lush beard, the hand with five fingers and one thumb holding the tiny glasses: it was a masterpiece and a snip at $9.99. I was tempted. But then I thought of all the other oddities I have acquired over the years and my wife’s objections to living in a cabinet of curiosities. Reader, I exercised discipline.

Do I regret leaving the painting behind? Almost. But I still have my photograph and, as Walter Benjamin wrote in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, the ability to mass produce copies has corroded the unique “aura” of originals and so diminished their value. I can look at Texas Dostoevsky any time I want. And yet I confess that the last time I was in Marble Falls, I visited the Goodwill store again, to see if it was still there. But no such luck. The painting was gone, hanging on an unknown wall, where it was almost certainly a portrait of somebody else entirely.

PART TWO: COME AND TAKE IT

My Last Sigh by Genevieve Daschenbach

“The eyes have it” as they say, and it was the eyes in the bold, naive portrait of “prolific mid-20th century painter” Genevieve Daschbach that captured my attention. So direct and alert, so frank and confident, and so very, very large. The portrait was so arrestingly strange that I barely noticed the street scene behind it by Daschbach herself, which was priced at $475 — highly optimistic at the best of times and especially so in a small town like Gonzales, where the first battle of the Texas Revolution was fought in 1835.

Indeed, so ludicrous was the price that I found the neutrality of the adjective in the note attached to the easel suspicious. Daschbach was not “celebrated” or “famous”, claims that implied some kind of value and which were falsifiable; she was simply “prolific”. Given that many completely unknown amateur artists could be described in these terms I wondered if this was not an act of mystification by the shop owners, justifying the absurd price through linguistic sleight of hand. But what to make of the bizarre detail that she had executed this final painting in-between trips to the toilet? And the innuendo that she may have died Elvis style, on the job?

The photograph is slightly out of focus because someone behind a partition was counting the day’s takings and I didn’t want to get into a conversation.

It all sounded like an elaborate hoax. And yet although the portrait was bad, Daschbach’s own painting was, upon closer inspection, not terrible. She had a decent sense of perspective, and I was reminded of L.S. Lowry’s paintings of “matchstick men” in industrial settings, although Daschbach’s style was less grim. Her painting looked like a nice street in an English coastal town.

Once home I did a Google search and found evidence in the US census of a Genevieve Daschbach who was born in 1903 and was living in a townhouse at 5448 Wilkins Avenue, Pittsburgh Pennsylvania in 1940. That seemed about right, although there was no word as to whether or not she was a painter. But then I found a French landscape by Daschbach that had sold at auction in 2016, while someone in the Washington DC area was trying to sell “outsider art” by Daschbach on Craigslist for $400. When I checked again a few days later the listing was gone. Did it sell? Was there in fact a secret demand for paintings by Genevieve Daschbach? Or had the seller simply given up and taken the listing down?

Regardless, I thought that the long note in the Gonzales antique shop mocking an old lady for painting on the toilet was a bit much. And later I dreamt about both the portrait and the letter, but I was in another shop and they were next to a different Daschbach painting — though how much that one cost in dream dollars I cannot recall.

Extreme Private Eros by Unknown

This large painting of a naked man leaning against a mantlepiece was hidden away in a back room of the same shop where I found Genevieve Daschbach’s final work. Gonzales, it seemed, was a veritable Klondike of questionable art. And as much as I was caught off guard by Genevieve’s bold gaze, so I was startled by this stark study of what appeared to be a high school geography teacher with no clothes on.

The model’s pose was awkward and uncomfortable, and he must have stood there for quite some time with his wedding tackle out, as the artist daubed away at his large expanse of skin and carefully clipped mustache. At first I imagined that they knew each other and that the painting was the product of a private ritual that had somehow leaked into the outside world. But the look on the model’s face suggested that he was bored by this particular trip to the naked rodeo. Perhaps he was a life model and this was simply an exercise in an art class.

But if so, what was the green velvet sphere doing on the chair? It had a hint of the uncanny about it.

I moved the tie, and lo, the double penis stood revealed. While the reflected penis was relatively undefined, the unreflected penis was visibly the product of some toil; attention had been paid to light and shade. And yet there was not a hint of eroticism in the artist’s gaze, rather there was blankness, void, the relentless, repeated application of lifeless paint. This was a flaccid phallus of cosmic ennui, crowned with the prickly pubis of eternal emptiness.

There was nothing I wanted less in the world. I replaced the tie, and turned my back on the geography teacher (and his penis) forever.

INTERLUDE: Faceless Robin

I found this un-portrait of Batman’s sidekick Robin in a Salvation Army in Round Rock last Christmas, close to a stack of adult diapers. That’s all I have to say.

PART THREE: THE TALE OF MARTHÉ

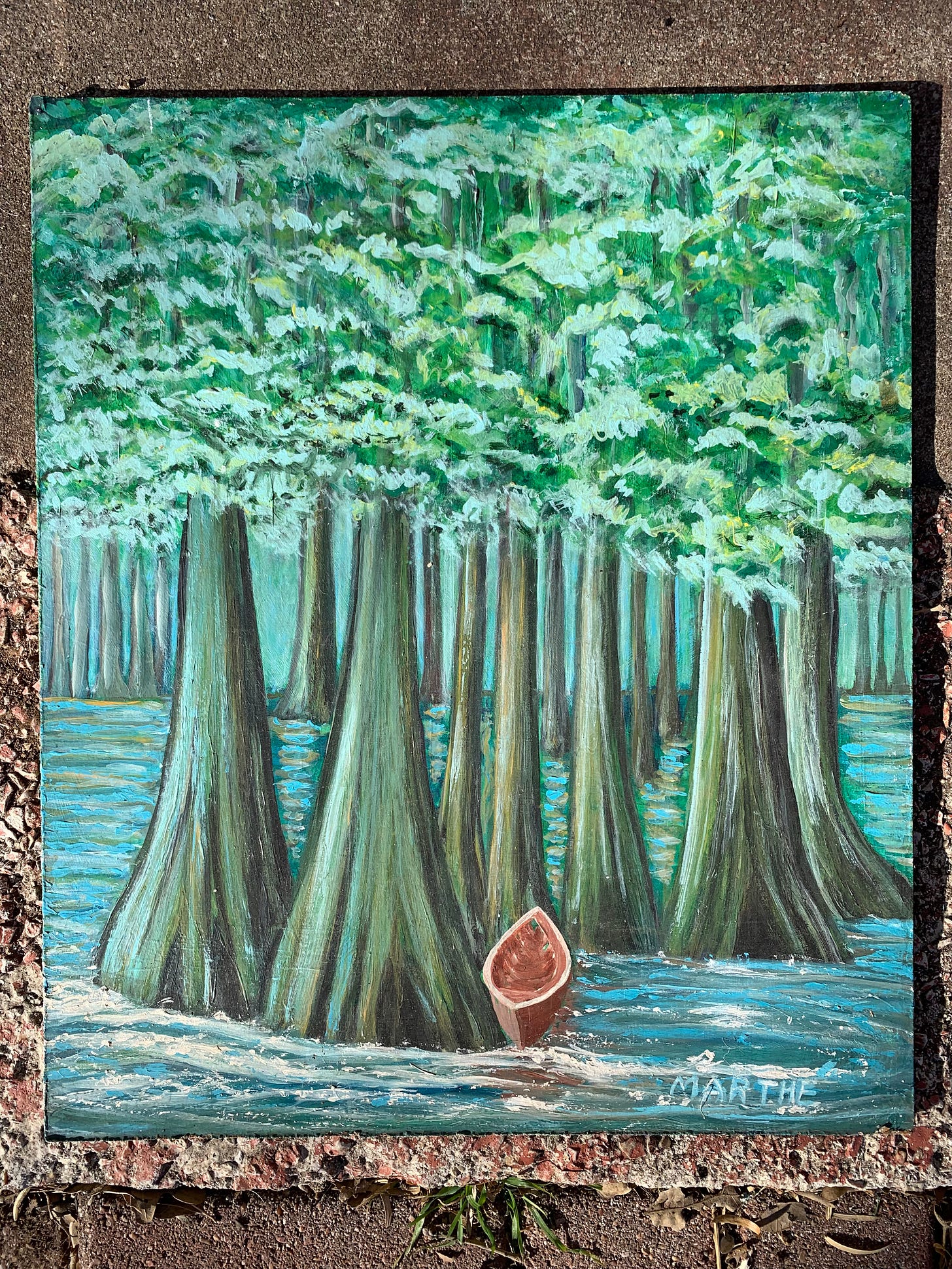

Floating Forest with Gash by Marthé

A few miles south of Austin, just beyond the town of Bastrop, there once stood a house in the woods. It was built to the specifics of the owners who had lived a good life there, surrounded by the kinds of books and records that intelligent people with taste enjoyed between the 1950s and 1980s. But then he died and then she died and after that the house lay empty for a long time, until finally some relatives got around to cleaning it out so they could sell the property.

At the time I was attempting to stave off financial ruination through various side hustles, and I offered to liquidate the dead couple’s possessions in the hope that I could sell the mid-century Heywood Wakefield furniture and some other items for a reasonable profit. Not knowing anything about the liquidation business, I did not inspect the condition of the items closely, and so only discovered after the money had changed hands that the family had really let the house go. The furniture needed refinishing, the records were warped from the heat, the books were riddled with holes, and there were tiny little scorpions crawling about under the furniture. There was also a deep and invisible infestation in the house, and as I cleaned it out I would find myself scratching obsessively, like the drug casualty in Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly who imagines that he’s covered in bugs. Except my bugs were real.

Naked in the Rain by Marthé (from the collection of Sandy Carson)

The house was also full of art: on the walls, in cupboards, stacked up against furniture. It was all the work of the old lady who had lived there, and signed with her artistic nom de plume “Marthé” (her actual name was Martha). Marthé, however, did not have any artistic talent, as is clear from the painting above. This image of a nude with distended legs standing in a dark waterfall with a plastic umbrella has many failings which are too obvious to list. The transparent umbrella is an odd detail, and leads me to believe that it was copied from a photograph in a magazine; the aesthetic is similar to that poster of the lady tennis player scratching her asscheek that was popular in the ‘80s. Yet Marthé through her clumsiness renders this similarly playful, kitsch image dark and bizarre.

But I think she recognized that: although I found something like 50 or 60 paintings in the house, human figures were rare and she only painted one face, which was mostly obscured by hair. Her preference was for landscapes, nature, the sea, although she wasn’t very good at those either. Interestingly, although the property was set on 100 acres of woodland, she never painted from nature but preferred to copy photographs in magazines, or to paint directly from her own imagination. Meanwhile, although she painted a lot and for a long time, I could detect no sign of progress in her art. She started bad and she stayed bad. Yet despite that she had continued to create for years, and so had left behind this large, unwanted oeuvre. I was impressed, even a little moved, by this commitment to her art in the face of a complete absence of talent.

I was also impressed by her husband who, no doubt inspired by a deep love for his wife, had been content to live surrounded by so much bad art. But then I remembered that he had died before her and it was entirely possible that her art had only exploded onto the walls after he had taken the leap into eternity.

Verklärte Nacht by Marthé

The work was unsellable, so I transported Marthé’s lifetime’s worth of self-expression to Goodwill in the back of a U-Haul, along with some chairs her husband had made that were falling apart. I remember that the guys unloading the U-haul truck were distinctly displeased as I unloaded dozens of canvases on them. Did you do these yourself? one of them asked. No they’re from a house in the woods, I replied.

But at the last minute I couldn’t bring myself to consign all of Marthé’s works to the thrift store. Somebody had to remember that she had loved art and that she had plugged away at it day in day out, year after year, even though she lacked all ability. Well, perhaps that’s a bit too much: Marthé did occasionally stumble upon an arresting image. I was particularly impressed by a surrealistic submerged forest with a floating gash-boat (which I placed at the top of this section) and the somber mountain above, emerging from rolling sea-clouds to meet the blank gaze of an avenging pink moon. I selected those and a few others for my own private collection; then I drove away. One year later, a huge fire ripped through Bastrop, destroying entire neighborhoods and swathes of the state park and, I imagine Marthé’s house, erasing the last evidence of the good life that had been lived there.

I barely broke even on the liquidation. I did, however, manage to sell three of Marthe’s paintings, at an estate sale in Austin that I organized. I gave each painting an evocative title, and wrote little cards like the kind you see in galleries, giving a brief description of each image that ended with the legend by Marthé, a central Texas painter who lived in Bastrop, offering no explanation beyond that. The price was $15 per canvas. A Chinese couple, captivated by their raw, mysterious power, spoke quietly to each other. I could tell that they were on the verge of making a purchase, so I walked up to them and gave them a little spiel about Marthé’s dedication to her craft that pushed them over the edge. They bought all three, without haggling.

And I hope that those paintings are hanging in their house to this day; because the ones that I own are still in my garage.

Thank you for reading Thus Spake Daniel Kalder. Hit the like and share buttons to help spread the word to the uninitiated. Also, don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t done so already. Regards, DK.