Happy New Year!

And what better way could there be to kick off our next cycle round the sun than by writing about death? You may recall that in November I described how a heightened awareness of mortality that set in during my mid-40s led me to change my approach to reading, making me more focused and systematic in my choices. But that was just scratching the surface: the truth is, contemplating my final voyage across the river Styx with Charon has proven to be useful in many other areas. In fact, the more I apply the death filter, the easier it becomes to make quick decisions about what to spend my time on, and to ignore all manner of bothersome nonsense.

As the new year gets underway, I encourage you to do the same. To demonstrate just how handy the death filter can be, I have compiled a few examples of it in action below.

Effective Altruism

I’m not sure when I first heard this embarrassingly clunky term, but I didn’t realize exactly how uninterested I was in it until a year or so back when I was asked to write an article about an argument between some philosophers on the Internet. One of these wise sages was an Effective Altruist, and although I attempted to muster some interest in his writings, it all seemed like warmed over utilitarianism to me. Now it’s possible there was a little more to it than that but I found the idea that our era was privy to some deep moral wisdom that had eluded all previous generations so ridiculous that I declined to investigate the matter any further.

Now, were I twenty years younger I might have had the patience to learn more about this fad so that I could know better how my fellow mortals were wasting their time. But at this stage in life I have more valuable things to do, such as mowing the grass, and so I declined the commission. I remained vigorously uninterested when crypto bro Sam Bankman-Fried wound up in court and the media started reporting that some of his crimes were inspired by his commitment to Effective Altruism. My suspicion was that it was all a post hoc rationalization for things he would have done anyway, and so via a combination of Occam’s Razor and the death filter I once again spared myself from unnecessary boredom.

I will confess, however, that when OpenAI nearly self-destructed because an Effective Altruist on the board was worried that their probabilistic word-generator might develop super intelligence and wipe out humanity (or something along those lines) I was briefly tempted to take a closer look. Perhaps Effective Altruism was less superfluous than it seemed, and was actually a wacky cult — like Theosophy, for instance. But Theosophy is more fun: Madame Blavatsky had a baboon, and even then I still wouldn’t read her writings. Perhaps if I had 200 years to live, but to judge by the lifespan of my grandparents I only have between 15 and 30 left to go — so thanks but no thanks.

Christopher Nolan films

It’s fairly obvious that this is not a golden age for the arts, and it’s painfully obvious that this is the case when it comes to cinema. Yes, superhero films have long outstayed their welcome, but the arthouse isn’t much better, as demonstrated by the fact that Christopher Nolan is supposed to be the great auteur of his generation.

Back in the ‘90s and early 2000s when I was in my twenties I watched almost every art or cult movie that came out, regardless of who made it or where it had come from. Indeed, I remember when Nolan first appeared on the scene with Memento, a diverting thriller about an amnesiac bent on revenge. That film showed promise, while his next movie, The Prestige, suggested that he might be destined for greatness. But then Nolan went off and made Batman Begins, a nonsensical film about a billionaire who dresses like a bat and drives around in a special bat car looking for bad people to beat up. It was ridiculously grim for such a childish concept, and although I was still pretty young I already realized I was no longer young enough to dedicate any more hours of my life to angst-ridden takes on characters that also appeared on little boys’ underpants.

After that Nolan made a few more Batman movies which I skipped, as well as the incoherent Inception which I watched in the hope that it might be a return to the form he had shown with The Prestige (it wasn’t). On the recommendation of a friend I watched the pretty but vacuous Interstellar and immediately regretted it. I ignored Dunkirk and Tenet, and by the time Oppenheimer rolled around I was completely inoculated against media hype. It’s not that Nolan is a terrible director—he’s a solid three stars out of five, which puts him ahead of most filmmakers today. But three stars does not give you a license to make three hour long movies; you need to have Tarkovsky/Fellini/Kurosawa skill levels to pull that off, and Nolan doesn’t. Indeed, I am yet to meet anyone who thinks that Oppenheimer was worth the three hours.

The elevation of Christopher Nolan, meanwhile, has led me to lose confidence in anything film critics say. If the greatest director of our era is a three star filmmaker, then it follows that everyone else is three stars or less, as a result of which I haven’t bothered with Triangle of Nothingness, Tar, Everything Everywhere All At Once, etc. Now, there are worse fates than watching three star art movies, and if I had to choose between reading about Effective Altruism or watching Oppenheimer I would pick Oppenheimer any day. But if I am to go the way of all flesh without seeing Nolan’s magnum opus (or any of the other films I just mentioned) then that’s fine by me.

Very long articles in American magazines

Back when I lived in Moscow, a friend gave me a giant stack of issues of The Atlantic —maybe two or three years’ worth. I had never heard of the magazine prior to that, but I remember sitting down and reading pieces by Christopher Hitchens and Andrew Sullivan and Michael Kelly at my kitchen table and — given my extremely limited access to English language media at the time — I actually managed to read every single one of the damn things from cover to cover.

Yet even back then, with so little to read and so much more of my life stretching ahead of me, I remember thinking: why are the articles so long? The features would frequently begin with incredibly verbose descriptions of a place or person before eventually fumbling towards the theme multiple paragraphs into the story. Although this vulgar display of “style” was supposed to signal quality what it actually resembled was a gibbon displaying its ass.

These days I am amazed when I see a copy of The Atlantic or The New Yorker (which also contains very long articles) in an airport or in Barnes and Noble because, aside from retirees, I have no idea who has the time to read all those incredibly long articles. There are so many more distractions than there were twenty years ago and when you apply the death filter, the ROI just isn’t there. Why read 8000 words dedicated to whatever Jeffrey Goldberg or David Renwick has deemed important, when there are too many great books to read already?

The Taylor Swift discourse

Yes, yes, she is a major cultural phenomenon and she made a billion dollars on her tour and Justin Trudeau pleaded with her to perform in Canada. Her last boyfriend made some jokes that upset some millennials and today she is dating some kind of sports person. She rerecorded her old albums to spite her old label. Her fans refer to themselves as “Swifties”. See? I already know much more than I need to and yet I never read anything about her. So no, I’m not reading your long essay on whatever Taylor Swift is supposed to represent this week.

Review pages

I used to dedicate quite a lot of time to reading the review pages in the Sunday papers, and at various times have been a reader of both the Times Literary Supplement and the London Review of Books. But that was a few years ago now: when you realize that you don’t have enough time to read all the great books that have already been written, then you definitely don’t have time to read many of the new ones listed in papers.

Of course, in a different era the review pages were not just a guide to what to read next. They kept you abreast of broader trends in the culture; whether or not you read any of the books, it was good to keep up with the conversation. The same went for films, and music. But it’s been a long time since novels were culturally significant; today the conversation is elsewhere — in technology, or with Taylor Swift (see above) or on YouTube in a video made by a guy I’ve never heard of but who has a billion subscribers.

Regardless, I might still keep an eye on the review pages if I thought that I might discover some witty novels or works of non-fiction that grappled with the absurdities of our times, but this is an age of fear and conformity, so that is unlikely to happen. Nevertheless, if a contemporary book were recommended to me by someone whose judgement I trusted then I wouldn’t hold its newness against it. But, as time’s wingèd chariot hurries near, I no longer have the time to trawl through thousands and thousands of words dedicated to things I am never going to read.

And so I don’t.

Cults

For many years I was fascinated by cults. Perhaps this was a result of being young in the 1990s, as the end of the millennium brought with it much strangeness and tragedy. This, after all, was the decade of David Koresh and the Branch Davidians, of the Aum Shinrikyo subway attack and the Heaven’s Gate mass suicide. So interested was I in sects and messiahs that in the 21st century I would scale a mountain in Siberia to speak with a traffic policeman turned Son of God, and also make several pilgrimages to the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, where I met some of Koresh’s followers (and a rival).

I knew the literature and had interviewed scholars; I was even something of an expert myself. And yet, as I edge closer to eternity, I find my interest in cults waning.

When streaming channels initially started making documentaries about every cult they could find I was on board: Heaven’s Gate: The Cult of Cults and Wild Wild Country were excellent. A Sinister Sect: Colonia Dignidad was pretty good. But Holy Hell, The Family and The Vow were less great, although I watched them to the end. Then I tried to watch Love Has Won: The Cult of Mother God, which was about a former McDonald’s worker who invented a cosmology in which Robin Williams was a divine being and who believed that she would never die, only to die. About fifteen minutes in, I found myself giving up completely.

All the bizarre ingredients were there, but all I saw was a motley collection of lost souls who were only talking to a camera because HBO needed content. This wasn’t a cult that I had heard of or which had ever had much influence. Meanwhile, without even watching the documentary, I knew in detail how the story was going to play out.

The overproduction of cult documentaries is starting to resemble the overproduction of superhero films; all the big characters have been done, so it’s time for Blue Beetle or Moon Knight as studios seek to squeeze just a little more juice from the theme before it dries up completely. Those fifteen minutes of Love Has Won triggered the death filter, after which I knew that I had had enough of cults for one lifetime, and that it was time for new things, or to go back and deepen my familiarity with old things.

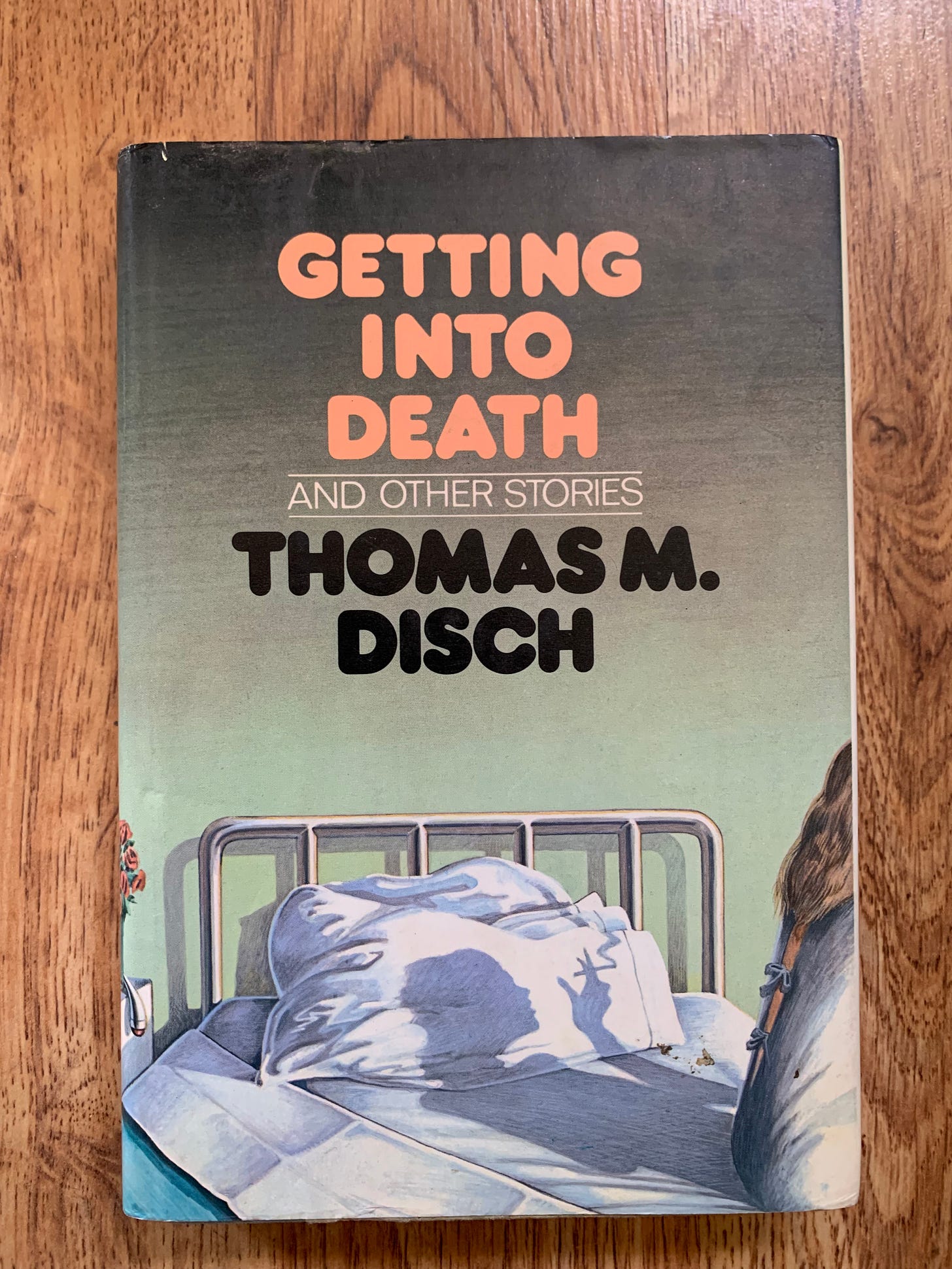

Getting into death

To be clear, this is not simply a list of things I am uninterested in, like skiffle music, horse racing or politics as a substitute for religion. Rather, it is a list of things I might have spent time on in those days when I felt as though I had all the time in the world. And maybe, if I had more time, then it wouldn’t feel like a waste to learn about one more cult, or to study the details of Effective Altruism so I could know better the peculiar follies of our day.

Yet a sense of diminishing time is no bad thing if it liberates you to care less about distractions, and to focus on the things that you knew were important all along. And we all know what those are: good books, shooting the shit with friends, listening to Bach’s Goldberg Variations, spending time with family, or flaneur-style wanderings in the abyss. Well, those are things I like, anyway; you will have your own preferences. But I guarantee you that whatever they are, when you apply the death filter, they will shine even more brightly.