TSDK No. 65. Hungry Freaks, Daddy

America's last rebel, bringing sexy back, the bitterness of Alan Moore and more.

Why what do we have here? It’s a fresh issue of TSDK, dripping with meaty goodness. Coming up:

America’s Last Rebel

Earth to Moon

Beauty Stab

The Galaxy

An Immense Sexiness

A Repudiation

Dog Breath Variations

America’s Last Rebel

For some time now, I have been thinking about writing an essay on the cultural significance of the late Frank Zappa. I first heard his music when I was about 16, and my enthusiasm for it has ebbed and flowed ever since, sometimes within the space of a single song. Zappa was truly sui generis, at once extremely talented and highly intelligent, but also willfully irritating and exceedingly puerile. He was also a man of relentless honesty, and I would have liked having him around during 2020-2022 when everybody lost their shit.

Anyway, after several years of contemplation, my definitive statement on Frank Zappa is now on earth. Everyone should read it, including those with no interest in or prior knowledge of Frank Zappa. The intro is below, the rest is at UnHerd:

Doubtless the fake nonconformist is an American type that goes back centuries, but we surely reached an apex of fraudulence in the early 2020s. How passionately the rioters of Antifa demanded the same things as Fortune 500 CEOs, how righteously millionaire celebrity “activists” raged for the machine. And there was something mournful too, about Bruce Springsteen and Barack Obama’s coffee table book Renegades, heavy as a tombstone marking the spot where Rock n’ Roll was finally laid to rest. The counterculture had gone full Weekend at Bernie’s.

Of course, it had been green around the gills for a long time. Confronted with the hyper-commercialization of radicalism in the early Nineties, the political historian Thomas Frank doubted that even its Golden Age amounted to much: “The Sixties was the age of postmodern fantasy and retailers’ dream, for each identity, each new phase of rebellion, necessitated a comprehensive shopping expedition.” The rejection of tradition, Frank argued, was simply the outcome of a desire to be free to flit between images: “They would be rebels, poets, perky-girls, English, hippies, and playboys in quick succession.”

But while there is much truth to Frank’s critique, the counterculture was not entirely bogus. Some hippies really did turn on, tune in and drop out. Hunter S. Thompson may have ended his days writing for Esquire, but all those drugs and guns weren’t going to pay for themselves. The cartoonist Robert Crumb really was a weirdo. And then there was Frank Zappa, guitarist, satirist, avant-garde composer, and writer of “Why Does It Hurt When I Pee?”

It’s difficult, now, to appreciate how famous Zappa was during his lifetime. Yet between the release of his debut LP Freak Out! in 1966 and his death in 1993 at the age of 52, his was a name you knew even if you had never heard his music — and you probably hadn’t, because it was never played on the radio. The one Zappa factoid everybody knew was that his children had strange names, Moon Unit and Dweezil being the strangest. These are tame by the standards of Musk’s X Æ A-Xii, but in 1969 the nurses were so scandalized by “Dweezil” (Zappa’s term for one of his wife’s “funny looking” toes) that they refused to put it on his birth certificate, and he was legally “Ian” until the age of five, when it was changed for good.

I first heard Zappa’s music after taping his concert film Does Humor Belong in Music? which was broadcast deep in the night when I was 16. I was amused by the dirty jokes, but it was also obvious that Zappa’s band had incredible chops. The small Scottish town where I lived turned out to be an outpost of Zappa fandom, and it was easy to get tapes and records. But you never knew what you were getting: Apostrophe was great and Hot Rats was sublime but The Man from Utopia was total crap and Jazz from Hell was unlistenable. Zappa always made sure there was something to annoy or offend everyone.

There was little in Zappa’s small-town Catholic boyhood to suggest he would one day become a counterculture icon. The catalyst for this grandson of Sicilian immigrants was his discovery of “Ionisation”, a dissonant, percussion-heavy piece by the avant-garde composer Edgard Varèse, which Zappa learned about when a hi-fi magazine described it as “the worst music in the world”. Intrigued, Zappa tracked down an LP and was astonished by what he heard. Teenage Zappa corresponded with Varèse and taught himself to compose with books borrowed from the library. He began writing his own orchestral music, funding his passion by drawing greetings cards, scoring films and running a recording studio. After a stint in jail for creating a tape of pornographic sound effects, he realized that if he wanted to hear the music he was composing, he would need a band to play it. He joined an R&B group called The Soul Giants and quickly transformed it into a vehicle for his own ideas, The Mothers of Invention.

The songs that Zappa wrote for The Mothers featured satirical lyrics that were right on the nose and complex music that could switch suddenly from polyrhythms and atonality to doo-wop parody. His timing was perfect: records like Freak Out!, Absolutely Free, and Weasels Ripped My Flesh fit right in with the mid-Sixties “freak scene”. But Zappa took his sound considerably further out than even his most psychedelic peers. In 1969 he released Uncle Meat, a bizarre collage of avant-garde instrumentals, tape manipulation, polyrhythms and spoken word excerpts, and also produced Captain Beefheart’s uncategorizable Trout Mask Replica. Even at their most experimental, The Beatles always made sure that their songs contained plenty of pleasing hooks and melodies, with the result that an ostensibly radical album like Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band still sold by the bucketload; Uncle Meat, not so much.

Read the rest here.

Earth to Moon

Speaking of Zappa, I recently read Earth to Moon, his eldest daughter Moon Unit’s recently published memoir. Readers of a certain age will remember her vocal on her dad’s only hit single “Valley Girl”, although my favorite Moon Unit performance is surely her turn as “Rusty’s California Girl” in National Lampoon’s European Vacation. In her book, Moon Unit does an excellent job of describing her highly unconventional childhood, as well as detailing the many disadvantages of being a “nepo baby”. As she puts it, even her name implies that she reflects her father’s light. One of the most impressive aspects of Earth to Moon is Moon Unit’s ability to remember what it was like to experience the world as a child, and to describe so much strange and aberrant behavior from that viewpoint. Funny, wistful and sad, but also (ultimately) wise, Earth to Moon is very good indeed and I highly recommend it.

Beauty Stab

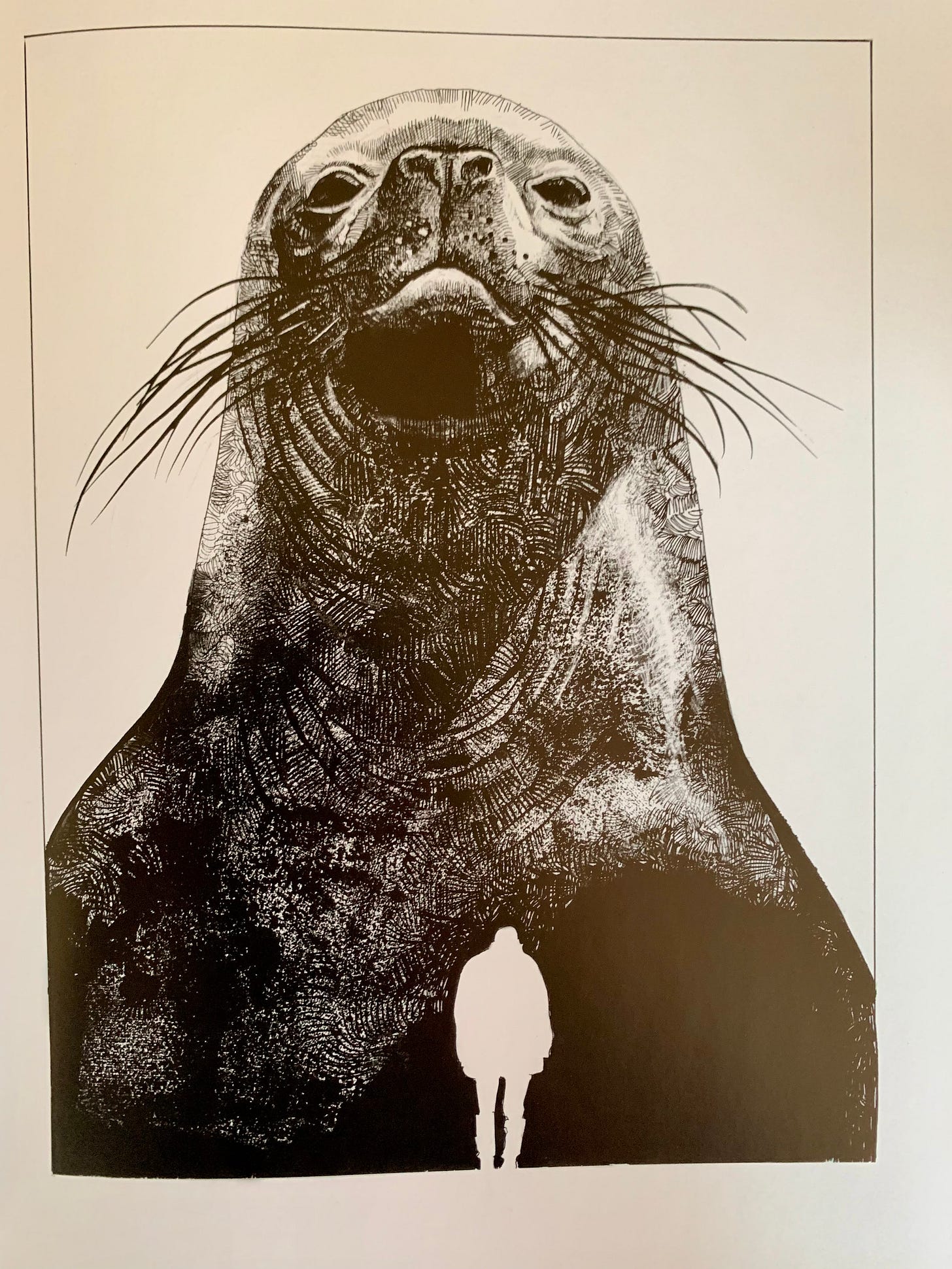

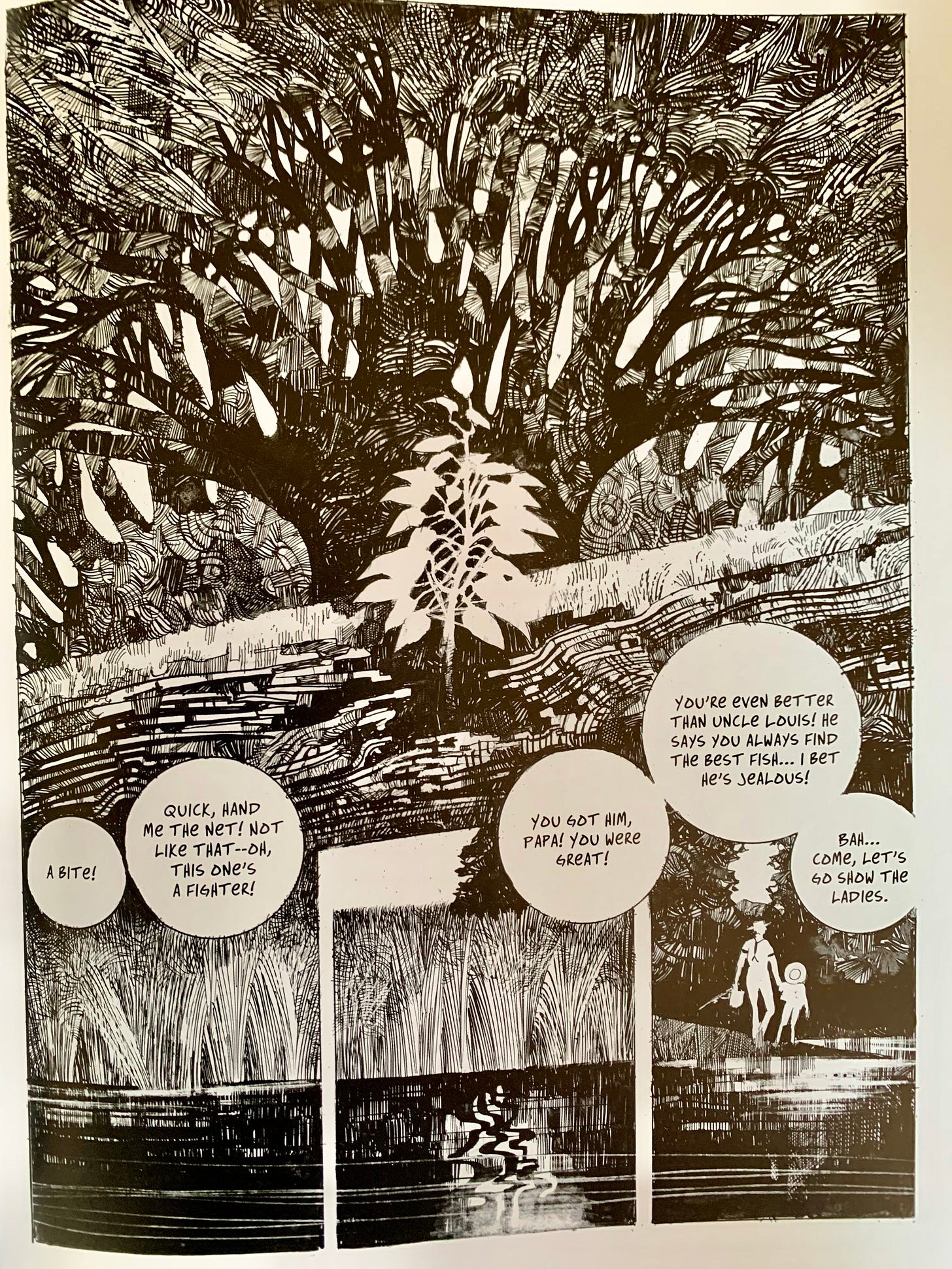

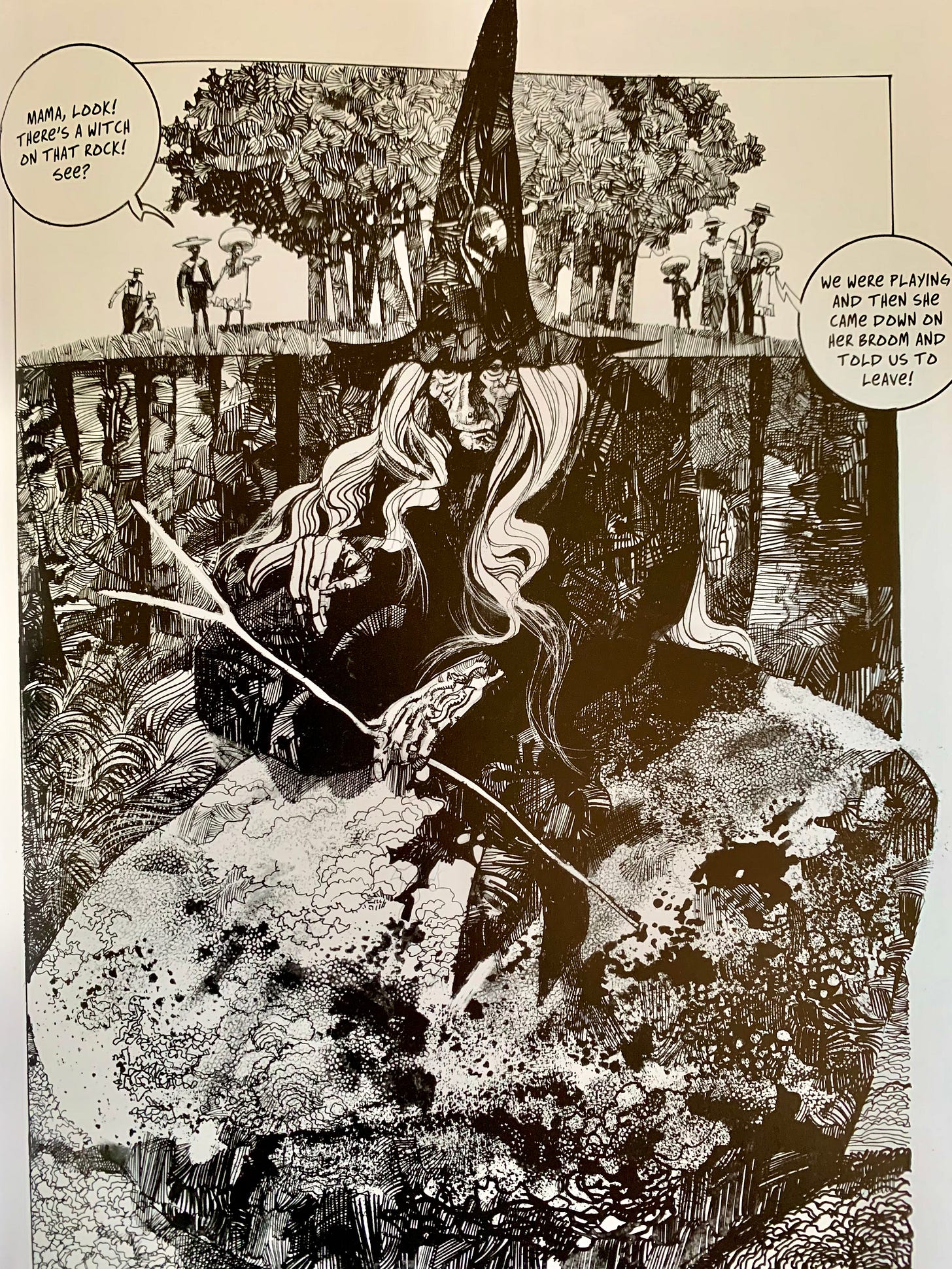

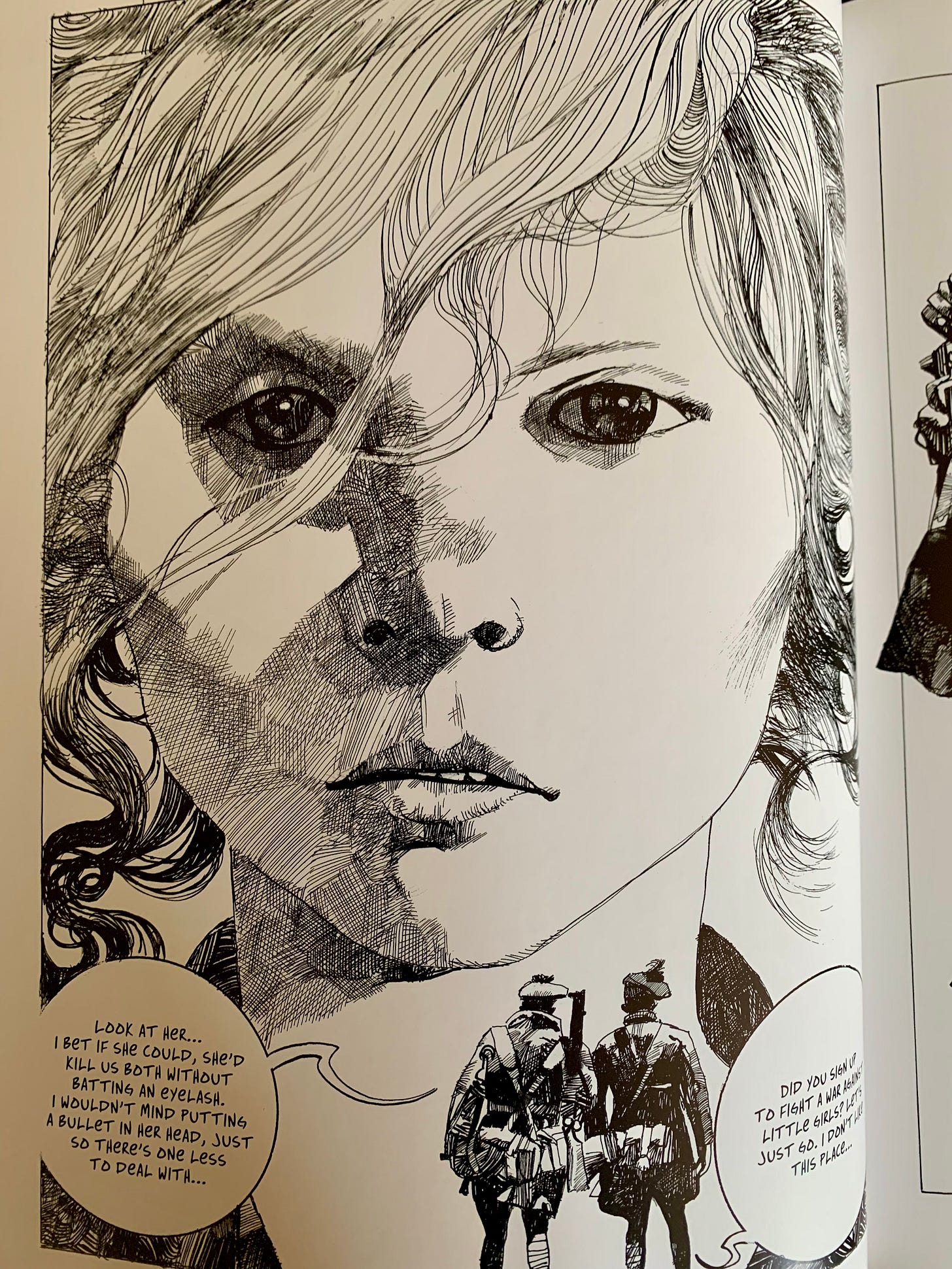

Since Zappa’s aesthetic was largely about ugliness I feel compelled to balance things out with some beauty. So here are some drawings by the great Italian illustrator Sergio Toppi, whose fantastical and historical tales are available in translation from Magnetic Press. All selections below are from the collection The Enchanted World. Every time I open the book I find myself thinking that if I could draw like Toppi, then that is all I would do all day.

From “Pribiloff 1898”

From “Brocelan Wood”

From “Brocelan Wood”

From “Black & Tans”

From “Black & Tans”

The Galaxy

In TSDK No. 64 I reminisced about the strange Cold War phenomenon whereby the BBC would broadcast bizarre animated films from communist countries at teatime. I continue to probe the depths of YouTube in search of these submerged relics, and of late the algorithm has been surfacing some truly obscure gems, including the marvelous Galaxy, by the Romanian surrealist Sabin Bălașa.

Galaxy is quite short — only seven minutes or so — and depicts the cycle of life on an alien planet, from the first appearance of forms in a barren void to the development of a mysterious child who grows and develops as he interacts with his strange environment. In Bălașa’s film the strange images come to life like moving paintings, revealing themselves only to suddenly change, and then change again. As a rule I don’t bother looking up the biographical details of the artists behind Eastern European animation — I prefer to leave them as mysterious as they were when I first encountered them on the BBC decades ago — but Bălașa’s work was so striking I had to know more. How had he produced such wonderful work under the miserable Ceaușescu regime?

In fact, there isn’t a lot of information available. I learned that Bălașa had the misfortune to be born in 1930, and was primarily a painter, influenced by surrealism. He seemed to have managed to escape the pressure to inject ideological messages into his films; no doubt their abstract quality served as a cover, and the authorities were free to project whatever political readings they wanted onto them.

Yet Bălașa did have to compromise. One of the few concrete details about his career I could find was that in the 1970s he painted portraits of Nicolae Ceaușescu and wife Elena at behest of mayor of Bucharest. He then found himself accused of glorifying the regime after it unexpectedly fell on Christmas Day, 1989. Bălașa defended his work, claiming that it was standard practice for an artist to portray kings and presidents and historic figures, though one wonders why he didn’t simply respond by asking his critics what risks they took to bring down the regime. “Yes I did it, I didn’t want to go to prison” might have sufficed.

Bringing Sexy Back

A Repudiation

Two years ago in TSDK No. 29, I wrote a mostly positive review of Alan Moore’s short story collection Illuminations. And while I suppose there are one or two good yarns in there, I now think I was far too gentle on the book’s centerpiece “What We Can Know About Thunderman”. This is a roman a clef about the comics industry which I described as “entertaining” if “caustic” yet which I ultimately “decoded with some amusement.”

Even at the time I had a feeling there was something more than a little wrong with “What We Can Know About Thunderman”, and in fact I now think it is a breathtakingly nasty piece of work that needlessly shits all over a group of people who for the most part did nothing to Moore, but who are mocked and ridiculed out of a generalized bitterness at the industry in which he made his name.

Having read and enjoyed Moore’s work since his early days scripting the likes of Abelard Snazz, the Man with the Two Story Brain for 2000AD, I was no doubt trying to hard to like the book. But the truth is that however much he rages at all his publishers and snipes at his former collaborators, the work he did in the 1980s on the likes of Swamp Thing, Watchmen, Miracleman et al remains what he is best known for because it is his best work, and will likely long outlive his ventures into prose such as Illuminations or his epic novel Jerusalem.

So, not that anybody cares, but I hereby repudiate my earlier review. As Dostoevsky said: “Above all, don't lie to yourself.”

Dog Breath Variations

Alright, let’s end with some atonality. As a rule, Zappa’s music isn’t very well known, but his orchestral music is especially not well-known. When I was younger I had no idea what he was up to, but having listened to many of the composers he was influenced by I now have a much greater appreciation for it. I wouldn’t say that it is beautiful, but it is certainly interesting. Here is his composition “The Dog Breath Variations” which was originally performed by his band The Mothers of Invention in 1969 but re-orchestrated by Zappa decades later and performed by the Ensemble Moderne in Germany, mere months before he died.

That’s all for now. In the next issue of TSDK I shall reveal things hidden since the foundation of the world, although then again, possibly not.

Regards,

DK

In a boring world, you've got a fabulous eye for the truly weird, often funny, and worth noticing.

I was an early adopter of Zappa. I got a friend to bring back the US version of Freak Out back from Chicago for me. Unlike the puny UK version which was one disc, this was a mighty double album in a gatefold sleeve. Bought Uncle Meat as soon as it came out. It’s still playing in my head. I saw the Mothers live in Manchester in 1969.