TSDK No. 69. How the World Really Works, Episode III

Claude Shannon, Texans in space, too much diddling, a robot Rachmaninov and more.

Greetings

Coming up in Kalder’s cabinet of curiosities: a mixture of recent commissions plus some exceptionally fine obscurities for your edification and delight. Oh, do not ask, “What is it?” Let us go, and make our visit.

How the World Really Works, Episode III

A Planet for Texans

The World Diddling Championships

More Metal Machine Music

Peep Show on Skis

How the World Really Works Pt III

Last year I planned an epic series for TSDK in which I would explore the origins of the modern world via a set of interconnected essays on information technology, material science, semiconductors, economics, and so on. I had about five of the essays roughly plotted out, but alas I was much too busy to do justice to the writing, so I decided to skip the first two and go straight to the third and (in my view) most important one. I also decided to pitch it to UnHerd, as having an editor and deadline would force me to actually finish the thing. And lo, here it is!

About a decade ago, as my home city of Austin’s big tech transformation really got underway, I started to wonder if I understood where the modern world had come from. I could articulate the core tenets of all the major religions, discuss the history of ideas from Plato to Derrida, and even describe, in detail, the many line-ups of prog rock giants. Yet, besides a basic overview of Newton, the Industrial Revolution and the periodic table acquired in school, I was rather vague on the history of science and technology. I was one half of C.P. Snow’s “two cultures” prophecy writ large, and in this I was not unusual: most people I knew with an arts education knew little about science, and vice versa.

What did the people coding away in the glass towers know that I did not? What did they actually do, these data scientists and developers — and why did it pay so much better than what I did? Initially, I agreed with the argument, sometimes aired in The Guardian and other organs of correct thinking, that if our tech overlords were going to have such an outsize impact on society, they had a duty to study literature, history and philosophy. But then I realized that I knew nothing of their area of expertise, and was hardly in a position to criticize.

And so I began to read books about technology and the history of computing. Much to my surprise, they were very interesting. I learned about Charles Babbage and his Difference Engine; Alan Turing and his imaginary machines;and ENIAC, the first computer, which had to be literally “debugged” because the heat and light emitted by its 17,468 vacuum tubes attracted moths. I learned, too, about the 1947 invention of the transistor and “Moore’s Law”, which held that the processing power of a microchip would double every two years, even as costs remained relatively stable, a prediction that proved accurate for decades.

The biggest surprise, however, was discovering that many of the core concepts underpinning the information age were the work of one man: Claude Shannon. Every time you send a text, make a phone call, search the internet or stream music or video, you rely on ideas he was the first to develop. In terms of impact, he appeared to me to be on a par with Einstein (at least). Yet while Einstein’s name is synonymous with genius, Shannon’s is unknown to the broad public. His first biography wasn’t published until 2017, almost two decades after his death and 80 years after he published the first of two major works that would revolutionize how we do, well, almost everything.

The childhoods of people who change the world always seem mundane in contrast to their later achievements, and in this, Shannon was typical. Born in 1906, he grew up in Gaylord, Michigan, a small town surrounded by farmland. His father was a furniture maker and probate judge, his mother a teacher. As a child, he enjoyed tinkering with radios, and went on to study electrical engineering and mathematics at the University of Michigan. In 1936, he took a position as a research assistant at MIT, where he learned to program a “Differential Analyzer”, a mechanical contraption the size of a room that solved equations with shafts, gears, wheels and discs. The next year, he worked as an intern for the US telephone monopoly AT&T, which had been established by Alexander Graham Bell 60 years earlier.

Shannon now started to theorize about a different kind of thinking machine. The relay circuits in the telephone systems at AT&T were comprised of switches that could be switched on, allowing electrical current to flow, and off, stopping the current. Shannon then made a conceptual leap, applying a system of logical reasoning, developed by the 19th-century English mathematician George Boole, to circuitry. Boole’s binary system was based on true or false questions, and Shannon proposed that if an open circuit was used to represent one and a closed circuit to represent zero, then circuits could be used to perform logical tasks such as decision making and processing rules. In 1937, he articulated this idea in his master’s thesis, “A Symbolic Analysis of Relay and Switching Circuits”. Though no one realized it at first, he had laid the theoretical groundwork for digital computing. Today, it is recognized as the most influential master’s thesis of all time. Shannon was 21 years old.

“Though no one realized it at first, he had laid the theoretical groundwork for digital computing.”

In 1941, Shannon took a job at Bell Labs, the research wing of AT&T. During the war, he applied his mathematical skills to anti-aircraft targeting and was part of the team that developed the “X-system” which was used to encrypt communications between Churchill and Roosevelt. This work was significant in itself, but it was after the war that he continued the work of establishing the information age. In “A Mathematical Theory of Communication” Shannon set out to solve the problem of “reproducing at one point either exactly or approximately a message selected at another point”. The problem was that analog signals, such as the electrical waves used in telecommunications systems, were susceptible to noise build up: static, errors, interference and so on. But boosting the signal also boosted the noise, which had the effect of rendering the original message unintelligible when it arrived at the other end — for instance in a long-distance phone call.

Shannon’s solution was to shift the focus from waves and current and to rethink the problem: what, exactly, was being conveyed in a message? At first, he referred in a letter to the “transmission of intelligence” before settling on the word “information”. He coined the term bit (from “binary digit”) to describe the smallest unit of measure. Shannon showed that all information — images, text, sound — could be broken up into bits, transmitted as zeros and ones, and then reconstructed clearly at the other end, no matter the medium, whether phone lines or radio waves.

So ubiquitous now is the idea of measuring information digitally that it is difficult to believe it is so recent….

Read the rest here.

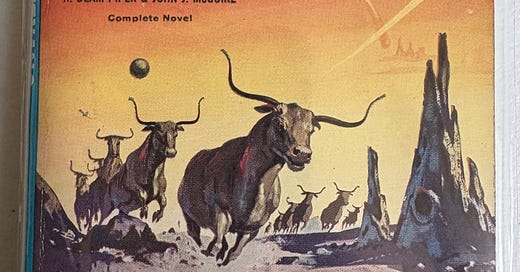

A Planet for Texans

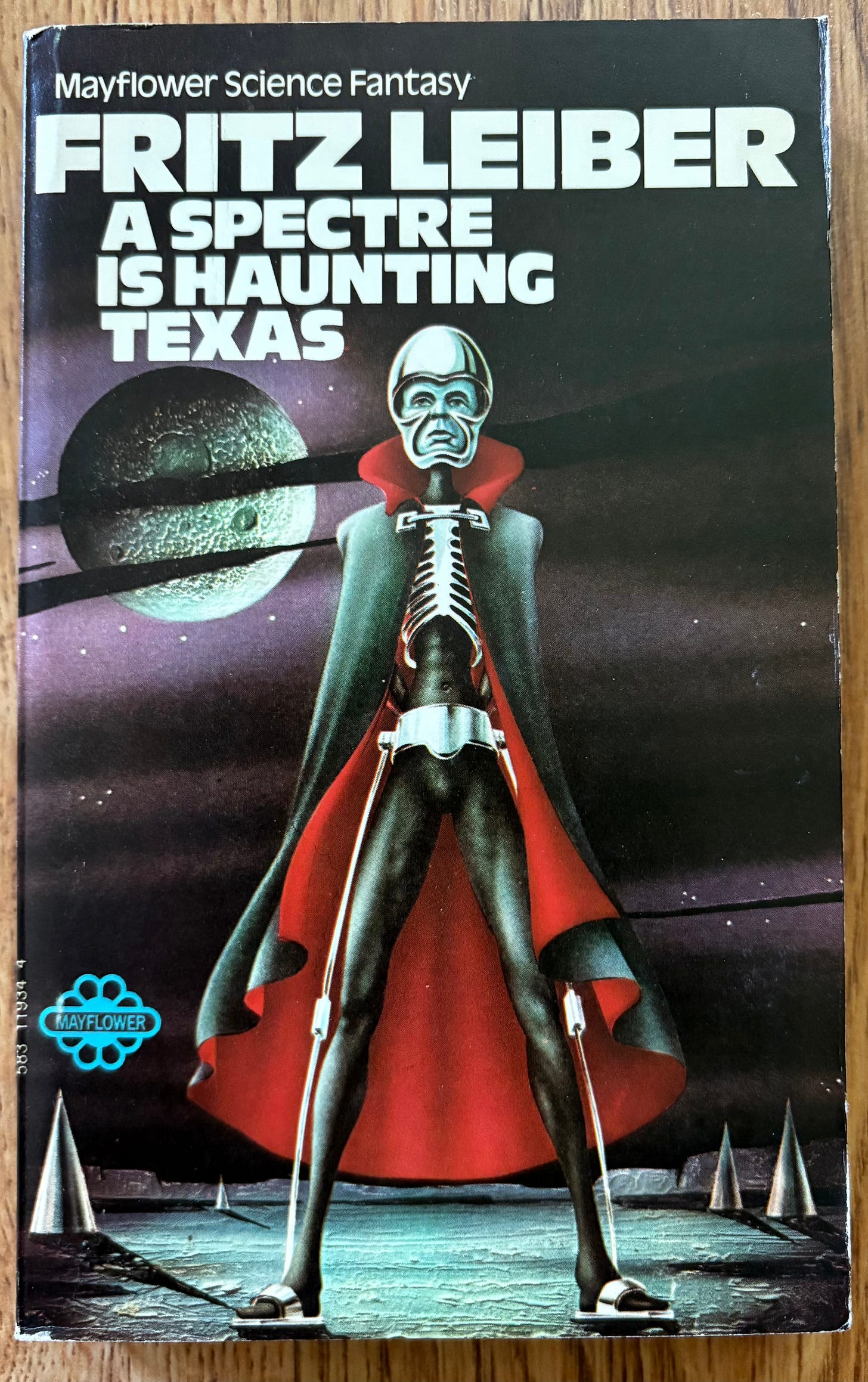

Is this the greatest book cover of all time? Signs point to “yes.”

A Planet for Texans was originally published in 1957 as Lone Star Planet in the SF magazine Fantastic Universe, and then as an Ace Double a year later (with Andre Norton’s Star Born on the flip side). Apparently the book is about a planet called Capella IV which is populated by Texans who rear giant cows and eat giant barbecues and where political assassination is legal (so long as it can be demonstrated that the victim “needed killin’”). I haven’t read it yet but intend to as soon as possible. And as H. Beam Piper forgot to renew the copyright, you can too — for free, at Project Gutenberg.

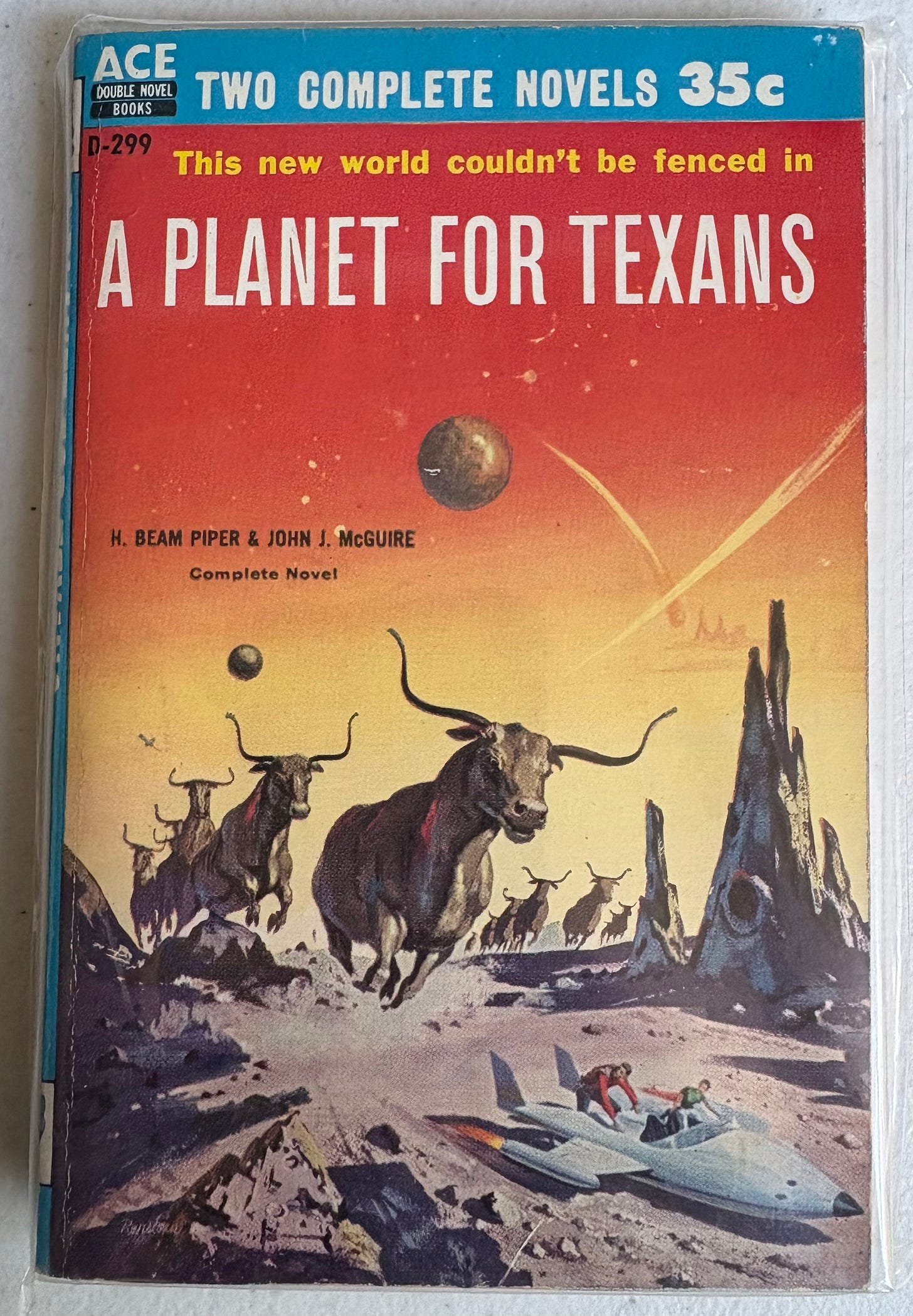

Intriguingly, A Planet for Texans is not the only Lone Star state-themed science fiction novel out there. After posting the above photo to Substack notes, I learned that, once upon a time, it was a whole sub-genre unto itself. For instance:

The Texas-Israeli War: 1999 was published in 1974 and is set in a world where Ireland doses the British government with LSD and the UK leadership proceeds to nuke multiple countries while tripping balls. The global population plummets, and Texas takes advantage of the chaos to secede from the rest of the US and take all the oil with it. To add insult to injury, Texas Rangers kidnap the president of the greatly weakened United States. At this point some Israeli mercenaries turn up and, in exchange for land, offer to rescue the president. But do they succeed?!? I don’t know, I based this summary on some reviews I read online. But I sure would like to find out.

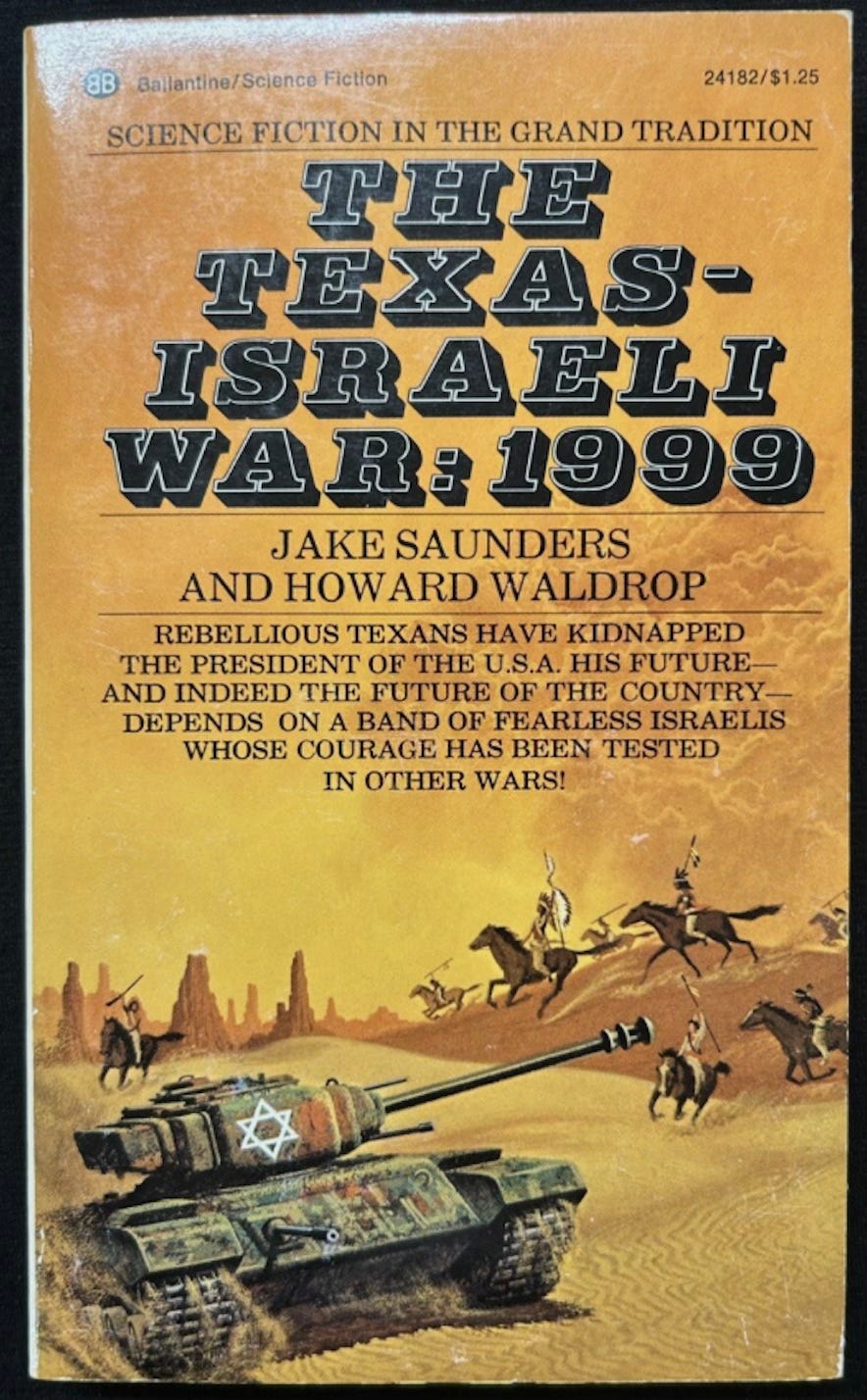

For Texas and Zed

This is another novel about a planet full of Texans, only this time they are living on a planet called Texas that orbits the star Zed in the year 2589. Planet Texas must defend its independence against the Galactic Empire and the Cassiopeian Alliance but unfortunately a Texican (sic) rancher kidnaps Lady Gwyn Ingles of the Galactic Empire, setting off a dangerous conflict that apparently threatens the planet’s survival. Kidnapping seems to be a thing in future Texas.

I know Fritz Leiber from his comic sword and sorcery novels featuring his characters Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser. An actor named Scully La Cruz arrives on earth from a colony in space thinking that he is in Canada, only to discover that it is now North Texas as the Lone Star State has annexed most of North America following a nuclear war. Not only that, but the Texans have engineered themselves to be eight-foot-tall good ole boys, and tower over their diminutive Mexican slave class. I don’t know about you, but it sounds like there might be some social commentary going on… Pictured above is the first UK paperback edition from 1971, which recently joined A Planet for Texans in my nascent Texas SF library.

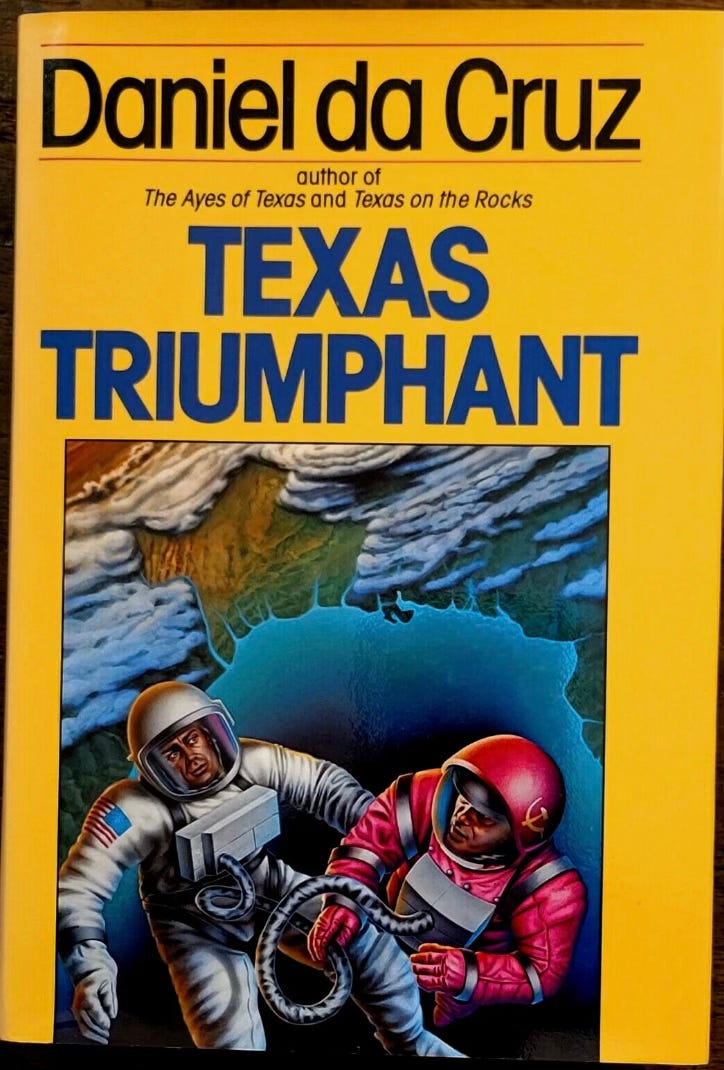

Finally, Texas Triumphant is the third part of a trilogy from the 1980s in which America falls and Texas is left to stand alone against the USSR. The Republic of Texas destroys Moscow with a nuclear bomb, which understandably annoys the Soviet leaders who retaliate with chemical weapons, or something like that. Intriguingly, the hero is a triple amputee World War II veteran. The cover, meanwhile, is a fine example of 1980s airbrush painting: back then it was everywhere, in ads, posters, book covers, comics. Slick as it is, it has a textural quality that cannot be reproduced by digital painting, and certainly not byAI.

As a naturalized Texan, it fills my heart with pride to discover this hidden canon. I fully intend to acquire all of these books, and if time permits, to review them in future issues of TSDK. And if there are any other Texas-themed SF novels readers are aware of that I have missed, please feel free to mention them in the comments!

The World Diddling Championships

So many, I had not thought diddling had undone so many.

More Metal Machine Music

In TSDK No. 67 I wrote about Folk Songs and Sentimental Ballads, an LP where all the sounds are generated by music boxes. But this is not the only recording I own where the “artist” is a mechanical automaton.

I am always intrigued by recordings of composers playing their own music, even if, given the fact that they were usually recorded on wax cylinders a century or so ago, the sound quality is typically not very good. Sometimes, the performances may not be all that good either — I once bought a CD of Bela Bartok playing his own piano compositions and learned from the liner notes that he actually made some mistakes!

Rachmaninov, however, is a different story. After leaving Russia in 1917 his ability to compose music largely deserted him; in order to support his family, he switched careers and became a virtuoso concert pianist, interpreting his own work and that of others. So when I found the recording Rachmaninov Plays Rachmaninov: The Ampico Piano Recordings (1919-1929) on the clearance shelves at my local Half Price Books I knew it would be good, if likely tinny. However the minute I put it in my CD player I knew something was wrong. The sound quality was excellent. The recording had clearly been made on modern equipment. As Rachmaninov had died in 1943, fourteen years before the release of the first stereo recordings, this wasn’t possible.

All was revealed in the CD booklet. Rachmaninov had never sat at the piano I was listening to; rather, half a century earlier he had played an Ampico “recording piano”which had captured his performance on paper rolls. Ampico engineers had figured out how to capture the effects of the pedals, and even the varying degrees of pressure Rachmaninov applied to each key, making it much more sophisticated than a simple player piano. If they felt the rolls had missed any nuance of his playing, they would retroactively edit them afterwards. Only when Rachmaninov was satisfied that the piano had accurately captured his performance would he sign off on the rolls. Saint-Saens and Debussy had also been recorded using this process. In the 1920s and 30s you could buy these paper rolls and have an automatic piano play the performances of maestros back to you in the comfort of your own home.

This recording I was listening to, however, was made in 1979 on a specially adapted “Estonia” piano. The rolls were loaded in, and then Rachmaninov’s ghost fingers sprang back into action, playing the likes of “Elegie in E flat minor” and “The Star Spangled Banner” for the first time in many decades.

The recording seemed completely ersatz to me. I wasn’t listening to the artist at all, but rather a bizarre simulacra. There weren’t even any hands involved; just holes in paper, mapping the data of his performance Some reviewers argue that the piano rolls capture the nuances of Rachmaninov’s playing, though how they would know that, given that no-one who heard him play is alive today, I have no idea. To me, the performances sounded cold, clinical, stiff. I tried several times to play the CD the whole way through but could never overcome the alienation I felt.

And yet, in preparation to write this, I decided to dig the CD out and listen again. And I have to admit, the first track was very sensitively played by the automatic piano. The Ampico engineers really did seem to have captured a lot of human nuance. The second track sounded fine too. And the third was’t bad either. Then I began to wonder: if I listened to this music blind, knowing nothing about it, would I even be able to tell that something wasn’t right, that it was played by an automato?

Probably not. And so the vanished hands of a long dead pianist played on, making the keys dance, the melodies ring out….

Peep Show on Skis

Also for UnHerd, I reviewed Mountainhead, the new film from Jesse Armstrong of Succession fame, about idiot billionaires squabbling with each other on top of a mountain. Armstrong clearly has only one mode, and it is in full force in this, his directorial debut:

Once upon a time, billionaires were boring. Warren Buffet drove a sensible car, lived in a quiet Omaha neighborhood, and made a fortune by investing in the world’s most uninteresting companies. Sam Walton was a wiry guy in a baseball cap who just happened to own Walmart, the largest retail chain on the planet. To this day, Bill Gates schleps around in a sweater, stupefyingly dull even as he sprays dust at the sun and expresses regret at all those meetings with Jeffrey Epstein.

Now, however, there is a new class of exceedingly colorful billionaire. Foremost among them is Elon Musk, the richest man in the world, close friend of Donald Trump, and father of 14 (that we know of). But there are many others: Larry Ellison, the orange skinned octogenarian CEO of Oracle, creepy Mark Zuckerberg with his plan to provide everyone with 12 AI friends each, not to mention Jeff Bezos 2.0, previously a standard issue ruthless oligarch, now a man given to posing with his shirt off and launching celebrities into space.

Not so long ago, the media gushed over these exotic creatures, convinced that they were going to lead us all into a new golden age. Tony Stark was the pop culture avatar of the charismatic tech genius, solving impossible problems with his brilliant inventions. But then things went sour: Trump, social media, disinformation… By the time OpenAI launched the generative AI revolution with ChatGPT, advances in technology were met with as much apocalyptic panic as excitement. It didn’t help that Sam Altman and his fellow AI CEOs kept telling us that the technology they were developing was so dangerous that it might one day kill us all. Curiously, they kept building it.

Never before have we had so many outlandish characters among the world’s rich and powerful. And yet, despite the abundance of targets, satire that tackles the phenomenon of the 21st century tech billionaire is thin on the ground. HBO’s Silicon Valley did a fine job of sending up the quirks of VC culture, but it was content to stop there, and swerved the larger sociopolitical questions. Into this void arrives Mountainhead, a new film by Jesse Armstrong, best known as the creator of Succession — although British readers may remember him as one half of the writing team behind the cult comedy Peep Show.

On the surface, it is easy to see why Armstrong was drawn to the theme. In Succession he wove a saga of a family of vile narcissists vying for control of the media empire their aging father, a diabolical combination of Rupert Murdoch and King Lear, was unwilling to relinquish. Succession served as a vehicle through which he could explore large scale questions regarding the media, politics and the corrosive effects of power on human relationships. In Mountainhead, Armstrong applies the same approach to our new billionaire overlords. The setup is simple: four tech oligarchs are spending a weekend at a mountain retreat in Utah, part of a tradition where they kick back and enjoy simple pleasures like burgers and beer, with no business talk.

Ven, played by Cory Michael Smith, owns a social media app called Traan and, as the richest man in the world, is an obvious analog for Elon Musk. Steve Carell plays Randy, the second richest man in the world, who is nevertheless powerless before his cancer. With his propensity for philosophizing and his wide range of contacts in the industrial military complex, he is most reminiscent of Peter Thiel or Alex Karp of Palantir, though not a direct riff on either one. Ramy Youssef plays Jeff, the most grounded of the four; his company provides safe AI. Jason Schwartzman plays Hugo, the much put upon owner of the Mountainhead retreat, who, as the creator of a meditation app, is merely a centimillionaire…

Read the rest here.

That’s All Folks

Thank you for your kind attention! I shall be back soon.

Regards,

DK

As a naturalized Texan, I'm also very excited to find out about this sub-genre!😆

Great essay.

Leiber’s “Conjure Wife” and “Our Lady of Darkness” have always appealed to me. Great article. Took me back with the cover of ASIHT.